The Blind Man; Blindness and Insight (2010), GCGCA(i)

Blindness and Insight

Institute of International Visual Arts, 33 West 67th Street, New York

22 Dec 2010 - 20 Mar 2011

‘Once the idea of the piece is established in the artist’s mind and the final form is decided, the process is carried out blindly. There are many side effects that the artist cannot imagine. These may be used as ideas for new works.’

- Sol LeWitt

Art, the word, the concept, the actuality, in its generic or its collective singular sense, comes into existence in European languages only in the last decade of the eighteenth century in early German Romanticism out of a certain relationship between philosophy and literature. One of the enduring mysteries of cultural understanding and terminology is what happens in the nineteenth century such that the term 'art', which originally comes into existence in a generic collective singular sense to mean 'literature' in Romanticism, by the beginning of the twentieth century means what we now call 'visual art’, in its exclusive opposition to literature.

And yet ‘visual art', as a category, comes into existence precisely at the moment in which so-called ’visual art' is no longer constitutively visual; when visuality (or indeed on occasion, its visibility) had ceased to be the defining function or character of art. Contemporary art is often referred to as 'visual art' in the singular (and equally the 'visual arts' in the plural), but what is meant institutionally by 'visual art' is an art that is practised within the terms of the institutions devoted to what used to be called 'fine' or 'beautiful art’. The class history of the translation of 'beautiful' as 'fine’ - of the ‘Beaux-arts’ as 'Fine arts’ - has meant that it has taken two hundred years for institutions to try and finesse the class dynamics of the association of those artistic practises with other class-based forms of culinary consumption - such as fine wines and fine food. 'Visual' functions in relation to this discourse as the term which has allowed the displacement of the embarrassment of the word 'fine'.

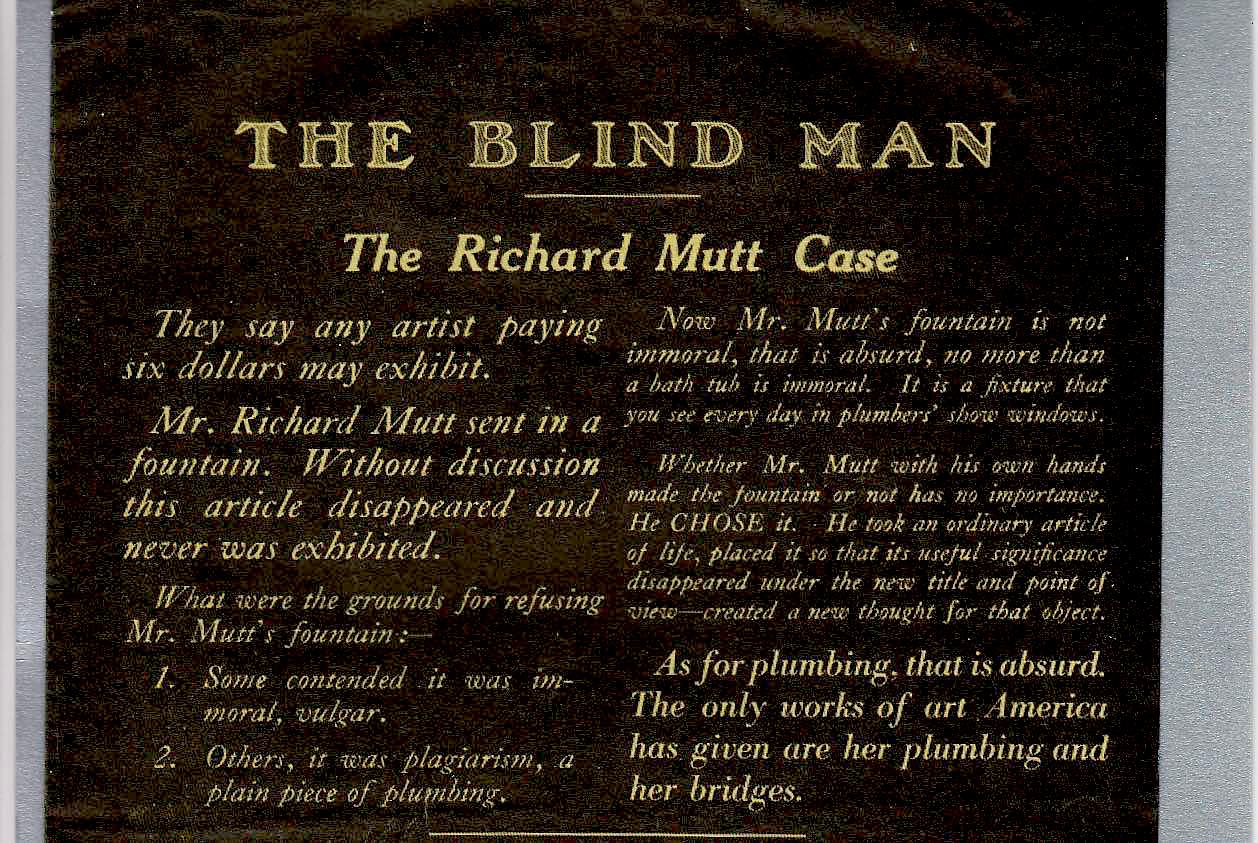

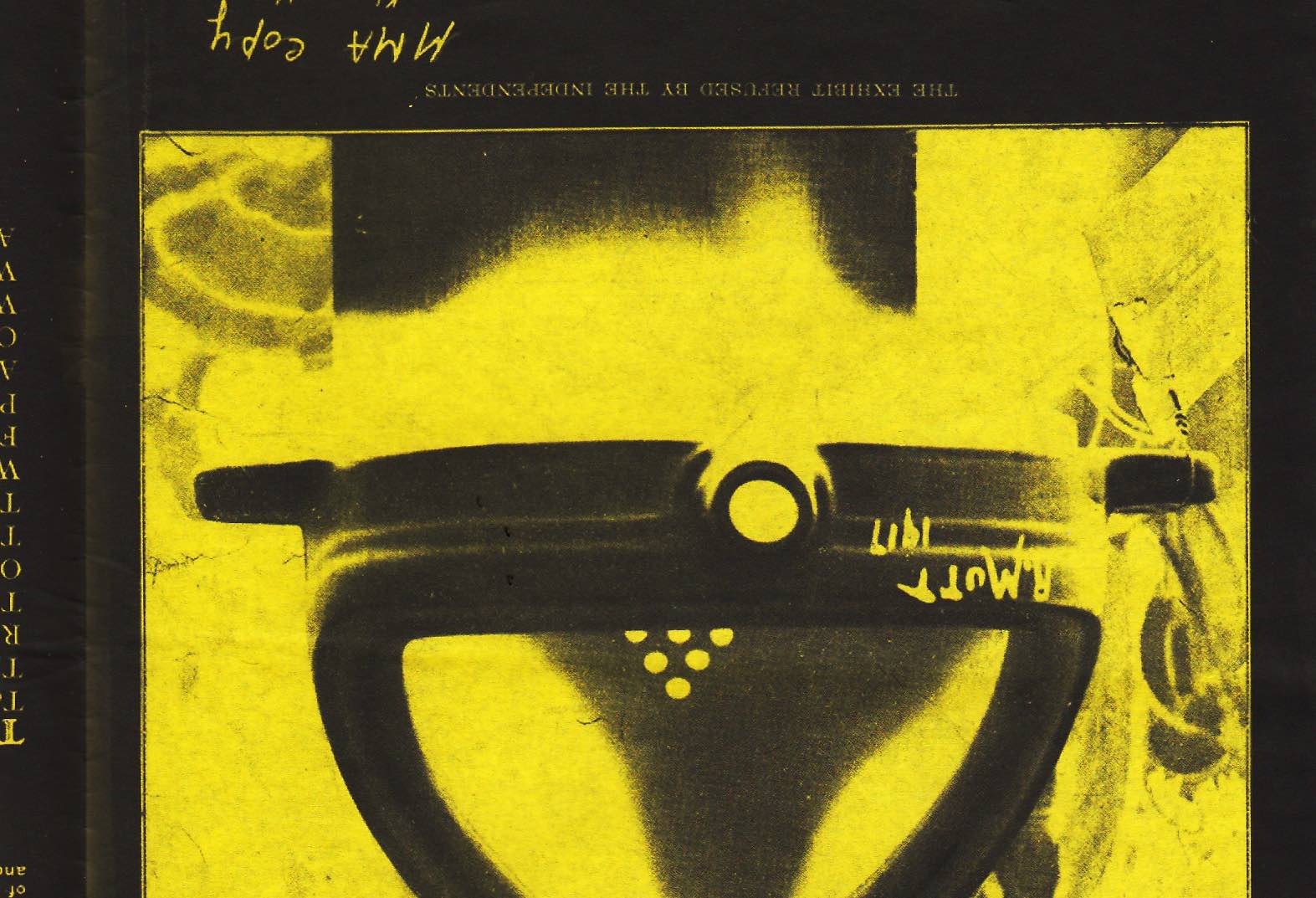

The Blind Man: The Richard Mutt Case; Blindness and Insight (2010), GCGCA(i)

The Blind Man: The Richard Mutt Case; Blindness and Insight (2010), GCGCA(i)